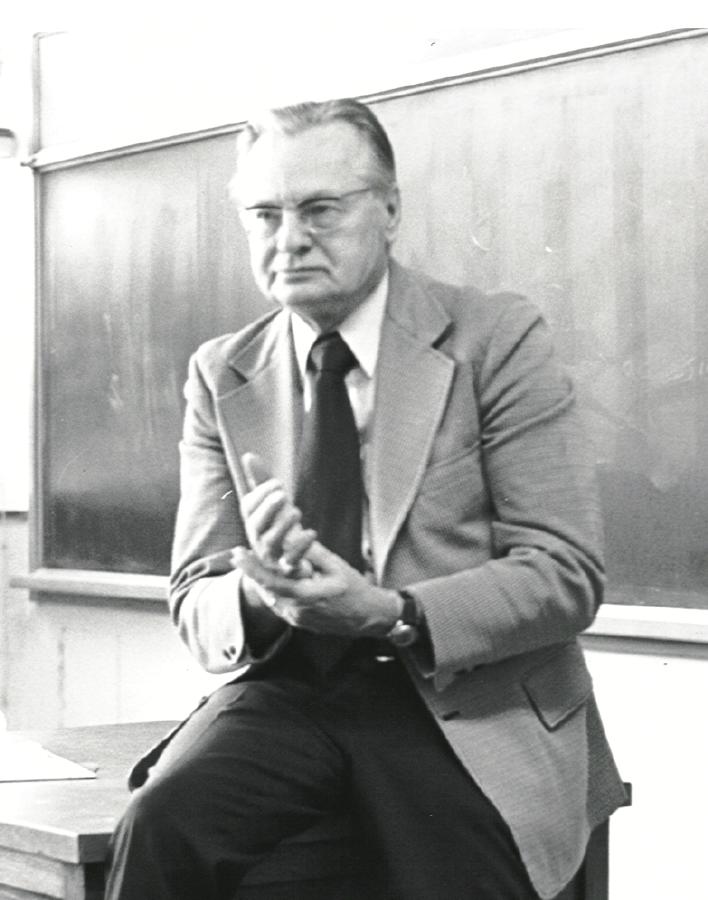

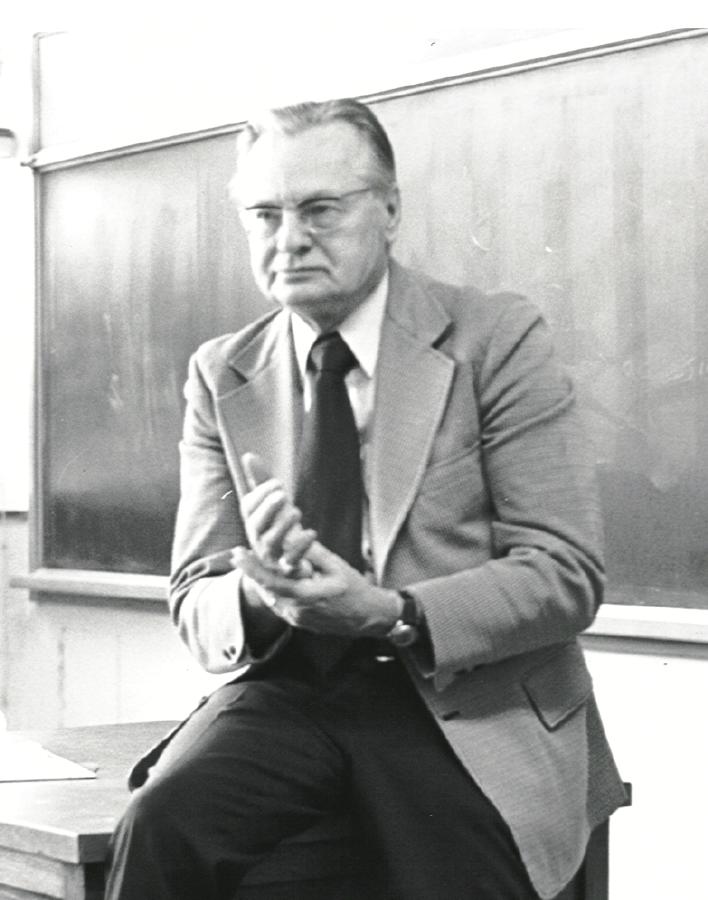

at Washburn University for many years:

_____

_____

C. Robert Haywood author of The Preacher's Kid

_____

_____

C. Robert Haywood author of The Preacher's Kid

I have always called him "Dean" Haywood, because he came to Washburn University as Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences in 1969, a few years after I began teaching there, and, though he was also Vice President for Academic Affairs and then Provost, for a faculty member there is no higher position than Dean of the College--he is "the dean," the other people merely administrators, hardly worth paying any attention to.

C. Robert Haywood grew up on a farm in Ford County, Kansas, south of

Dodge City, during the "dust bowl" period, the setting for The

Preacher's Kid, a set of stories told by Bobby Woodward--a boy the

author insists is not autobiographical. He went on to Dodge City

Junior College, then, after time in the Navy during World War II, went to

the University of Kansas for his B.A. (1947) and M.A. (1948) in

history. He taught history at Southwestern College in Winfield,

Kansas, for some years, then, after earning his Ph.D. at the University of

North Carolina (1956) with a dissertation on Colonial Mercantilism, became

Dean of Southwestern, and then of Millikin University, Decatur, Illinois,

before coming to Washburn in that capacity. But he was always first

a teacher, and returned to the classroom as distinguished Professor of

History at Washburn for several years before his retirement. Over

the years, he has been very popular as a speaker, has published widely in

academic periodicals, and has a series of books on the history the Dodge

City region--Trails South and Cowtown Lawyers

with University of Oklahoma Press, and The Victorian West

with the University of Kansas Press--but the Preacher's Kid

is his major work of fiction, published by The Woodley

Press (click link for ordering information) in 1985, and

winner of the Kansas Authors Club annual Coffin Award in 1987. As

the back cover of the book informs us:

Bobby Woodward tells of his

adventures and misadventures in coping with "Mr. Hoover's Depression" in a

small western Kansas town. He may be cursed with the added burden of

being a PK (Preacher's Kid), and with a FATE which could be either lucky

or unlucky, but he is certainly blessed with a penchant for finding

trouble and "tribulation," with a fine boy's soprano singing voice, and

with an older brother, who helps him "sort things out," regales him with

tales of bold knights of old, and encourages him "to own" all the big

words he can, which will then "mightily astound those college

professors." He brings this mixture of benefits and liabilities to

his contacts with school, the Methodist Episcopal Church-North, the Lucky

Mr. "Pretty Boy" Floyd, an unpredictable baptism, a Texas-style burying,

the town's profane blacksmith, a hasty marriage, tent shows, and the

traveling, mummified body of John Wilkes Booth. Over it all hangs

the dust, the Depression, and a growing awareness of life's farcical

victories and survivable defeats.

The book is a collection of a dozen stories, each standing on its own, but pulled together by the character and his environment into something like a picaresque novel. As a sample, I offer the next to last story:

The Deep Hole Swimming Champion of Kansas

Bud Taylor and I had plain run out of

anything to do. For about a half hour we'd been stretched out in the

shade of a puny cottonwood tree in his backyard, not moving or saying

anything. There was hardly a stir of wind in all that big open sky

we could see through the branches. The cottonwood leaves were making

a soft, sad whisper as the breeze oozed through them. A few lonesome

clouds floated along in the sky and, if we were doing anything, we were

watching them change shapes and colors. We had long since stopped

telling each other what they looked like. The day was too lazy, hot,

and quiet for us to be bothered.

It was hot! The big

thermometer in Sargent's Drug Store window registered 105 degrees at 11:00

o'clock that morning. I felt I could never work up enough ambition

to move away from that one spot. The whole town must have been in

the same mood. There wasn't a sound to be heard anywhere. It

was as if everybody had the day off and all had decided to take a nap at

the same time. Bud and I just lay there in the heat and stillness,

waiting for a new cloud to come into view, not really caring whether it

did or not.

After a while, Bud said, in

a sleepy voice, "I'll bet it's a lot cooler in the old jail than here."

I was so near to falling

asleep, I had a hard time concentrating on what he was saying. I

decided he meant the old Dalton jailhouse. It had been built back in

the horse-and-buggy days to hold prisoners overnight. If some drunk

got too rambunctious at the Parish Hall dance, or someone robbed the bank

late at night, the county jail was too far to take them there on horseback

until the next day. So, the town built this eight-by-ten-foot cement

house. The walls were about a foot thick and you could see the iron

reinforcing rods sticking out of the four corners. There was one

little window and a door made of strap iron. With the door sagging

open, it had stood for years empty and forgotten on the same lot as the

town's water works. I could see why Bud might think it would be cool

there because of the thick walls and cement roof.

"I don't know," I said,

starting an argument out of pure boredom. "A place that small, with

no air stirring, would be hotter'n the Black Hole of Calcutta."

Harold had told me how the

Sepoys had crowded all those Englishmen with their bulldogs into a little

dungeon over in India. I told Bud about it.

"Most of them went mad," I

explained, "foaming at the mouth or dying of the heat. It gets awful

hot in India even if you ain't in any hole. At least I think they

put bulldogs in the Hole with the Englishmen. I ain't positive

certain about that."

I remembered something

about only Englishmen and mad dogs going out in the noonday sun in

India. Logic would put them in the hot Hole together, but I could

have mixed up the story with some Kipling poems Harold also read to me

about the same time.

"If they put bulldogs in

with 'em, maybe they died of rabies," Bud suggested.

"That's dumb," I

said. "Dogs don't get rabies because it's hot. No, it was

because the space was so small."

We were both saying things

that didn't make much sense simply because we were too lazy to think

straight. But we kept at it until we had a fair argument

going. The only way to settle it was to walk up to the north end of

town to see for ourselves if it was hot inside the jail or not.

When we got there, we

forgot all about the jail, because there was some water spilling over the

side of the water tower. We had never seen that before. The

tower, actually a standpipe, had been there a long time. It was

built back before the World War and was about as big around as a

good-sized room. Its dozen coats of black paint always seemed to be

peeling off. Ted Barton had written an editorial about the standpipe

in the last Dalton Weekly News. He told how fortunate

Dalton was to have a good water supply, 99.9 percent pure, and how the

standpipe was one hundred feet and six inches tall and leaned a bit to the

south because the foundation had settled on one side.

"They had to take off the

panel there on top," Bud explained, pointing up to where the water was

dribbling over, "because the hinges were all rusty, and Shorty Wilcoxen is

putting new ones on. They need to get inside once in a while to

clean the blamed thing out. 'Skitter' told me that, last time they

scrubbed it down, they found two dead sparrows and a squirrel I

guess that's why the water is only 99.9 percent pure. But the reason

the water is spilling over is 'cause the panel's gone."

Since we had forgotten all

about our argument over the jail, and it was still scorching hot, I lay

down in the shade of the standpipe with my head up against the cold

iron. Looking up at the sky from that angle, the standpipe appeared

a whole lot more than a hundred feet tall. With the clouds passing

by, it felt like the pipe was moving and about to fall over.

Bud was just as impressed

with its bigness as I was and said so.

"I dare ya' to climb all

the way to the top and look in where the panel's gone."

"Wouldn't be no trick at

all if I could only get a boost up to the first rung of the ladder."

You see, there was an iron

ladder bolted to the side of the standpipe, but it was ten or fifteen feet

from the ground. They did that to keep kids from climbing up and

painting stuff on the sides. The high school seniors always managed

it anyway, just before graduation day.

Well, the more I thought

about it, lying there looking up at the standpipe moving against the

clouds, the more fun I thought it would be to take Bud's dare. Then

I got this crazy idea. Or maybe it was just the greatest idea I ever

had!

"Look here, Bud," I began,

getting more excited as I talked. "Do you realize there's a hundred

feet of water in that pipe? There ain't no place in Kansas where

water is a hundred feet deep. Man, alive! That's as deep as

the ocean a hundred miles out from shore. With the panel off the

top, a guy could climb up the ladder, kick out of his clothes, and be

swimming in the deepest damn swimming hole in the whole damned state!

Bud kept looking up, but he

began backing away.

"Think of it!" I was

up on my feet now, waving my arms around. "Nobody in all of Kansas

ever swam in a pond, or lake, or anything that deep. Now, if we

climb up there, we will do something nobody in all of Kansas, including

Wichita, has ever done. And we could do it right here in

Dalton. Man! Oh, man!"

I didn't know right then

how I was going to get up to the first iron rung, but I knew nothing was

stopping me from swimming in Dalton's standpipe.

"You're plain nuts," Bud

said. "As sure as ya' get halfway up, old Charley Fowler would come

and haul ya' down. But even if ya' got inside, suppose everybody

flushed their toilets at the same time or a fire broke out and they began

squirting all that water from the fire hydrant. Before you would

know it, the water would be down three feet and ya' couldn't reach the

edge to pull yourself out. You'd drown in there for sure."

Charley Fowler was the town

marshal, and he also tended the two wells pumping water into the

standpipe. It was true he checked around every once in a

while. I hadn't thought of that.

"We'll do it at night," I

said, getting rid of Fowler as an obstacle. As for everybody going

to the bathroom all at one time, although it presented a funny picture, I

didn't think the odds were very great that it would happen. But I

could see Bud wasn't nearly as enthusiastic as I was about being the only

person to swim in a hundred feet of water. I was going to have to

work hard on him.

"Look, we can get the

extension ladder off Wilson's garage. It's only down two

houses. Then, we can reach the bottom rung and, from there on, it's

just one step after another to the top. We can splash around a bit

and come right back down. Boy, I can just feel that cool water

now. Besides, we'll have done something Hottsey Winter never dreamed

of doing."

Hottsey was Bud's worst

enemy and I knew he would do almost anything to get the best of

Hottsey. I could see Bud was wavering.

"We'll do it tonight,

because they might have the panel back on tomorrow. Besides, there's

a big, full moon and no clouds." Funny how your mind covers up what

you don't want to think about. I'd plumb forgotten the clouds we'd

spent the afternoon watching.

We finally arranged to meet

at Wilson's garage at midnight, giving us plenty of time to see that the

folks were asleep and the moon up.

Everything worked out just

like I had planned. Wilson's ladder reached the lower rung easy

enough. I took off my shoes and started right up. When I

looked down to say something to Bud, he was gone. I couldn't chicken

out after getting that close, so there was nothing to do but go it alone.

Climbing up the ladder

'most took my breath away. Each rung lifted me up further from the

hot, dusty town and into the free, cool air. It was just like the

dream old Jacob he had when he beheld the ladder set upon the earth with

the top reaching into the heavens. The moon seemed to be floating

along just out of arm's reach and, honest-to-God, got brighter the nearer

I got to the top. I could see a few lights flickering down on Main

Street and a car moving along Highway 54 not making a sound.

Everything else was covered over with the night. You could see the

shape of the houses and trees, but they seemed soft, smooth, and rounded

off in a flimsy haze. The only sound I could hear was the wind

making a low moan as it slipped by the panel opening. I I never felt

so perfectly alone and so almighty calm in my whole life.

When I reached the panel

opening, I could feel the water slopping over the edge a little, as it had

been doing in the afternoon. I skinned out of my overalls, which was

all I was wearing, and splashed in. Oh, Lordy! Was that ever a

great feeling. The water was a lot colder than I had expected, but I

felt like a million even if I was covered all over with goose bumps.

I swam around the edge of the pipe, back and forth, and tried to shoot up

and touch the top of the standpipe cover. After about fifteen

minutes or so, I climbed back out and scurried down the iron ladder.

When I got to the bottom rung, I realized Bud, the damned coward, had

taken down Wilson's ladder. I let loose and dropped to the

ground. I got cuts all over my feet and picked up a dozen stickers

before I could find my shoes.

It wasn't 'til then that I

remembered that in all the excitement I'd left my overalls up on the rim

of the standpipe. There I was, naked as a bluejay except for my

shoes. To add to my troubles, a truck came up Main Street and turned

in by the well-house, with its headlights on the standpipe. I

flopped down in the weeds and hugged the ground while Charley Fowler, with

a couple of guys, went into the well-house. I knew I couldn't lie

there in the weeds all night while they drank their bootleg hootch and

swapped tall tales. I couldn't be scrambling around to get the

ladder back up to get my overalls, either. So I crawled along until

I thought it was safe to take off for home. I felt like a fool

running across Main Street in the dead of night as naked as the man from

Jericho before the Good Samaritan found him. I had to hide in the

bushes in Miss Sweetwater's yard to catch my breath, hoping no Samaritan

or anyone else would come along. I could have knocked Bud's block

off for hiding the ladder.

Once

I had sneaked back through the window, and was safe in my bed, I calmed

down and stopped shaking. After a few minutes, I forgot all my

immediate troubles: the lost pants, the ladder, the scratches all over my

body, and the sight I must have made streaking across town. I just

lay there in a kind of exhausted glow, knowing I was one of a

kind--knowing I had done something no kid, nor no grown up for that

matter, had ever done. I couldn't wait to lord it over Bud and brag

to the other guys about my adventure. It would make up for having to

wear knickers, being a PK, and having a Dad who wouldn't let me go to the

Toby Shows. I felt on top of the world.

Then

it hit me, like somebody punching me in the middle of my stomach. I

couldn't tell anyone, not even Bud, what I had done. If

they--meaning my folks, Charley Fowler, Ted Barton, Miss Carlson, the

Sheriff, anybody--found out about that swim, there would be all

hell to pay. They might go so far as to send me to the Hutchinson

Reformatory. But even if they didn't, I'd be in for it. I

wouldn't mind Dad swatting me with his belt, I could even stand Mom

crying, but I'd lose all freedom. They'd watch me like a hawk

forever. I'd have to go to Wednesday Night Prayer Meetings, would

never be let out of the house after dark, would find the screen nailed

shut, and God-knows-what-all. Then, too, I wasn't even sure Harold

would think it had been a great idea. I couldn't stand it if he got

sore at me.

Damn,

damn, and double damn! Here I had gone and done the greatest thing

in my whole life, big enough for Robert Ripley's BELIEVE IT OR NOT,

probably the greatest thing anyone had done in Dalton since the last

Indian raid, and I couldn't tell a soul. The more I fretted

about it, the more unfair it seemed. I was like the prospector in a

story Harold had told me. This guy had found a ton of

treasure--gold, rubies, diamonds, and stuff. On his way back to

civilization, he lost his pack full of gold, and his map, too. He

was fated to spend the rest of his life on secret missions, trying to find

the lost cave in the mountains. He couldn't tell anyone about his

fabulous find for fear they would beat him out of it. He died in an

insane asylum, crazy as a bedbug, foaming at the mouth, and jabbering

about gold and rubies, but by then nobody paid any attention to what he

was raving about.

I was in the

same fix.

This

was worse than that time in Wichita when Herb Wellington talked me into

thinking I was a born loser right when I thought I was a big winner.

That had been just a sad case of a goofy kid being lucky for once in his

life and me not. It could have gone the other way just as

easy. This time there couldn't be any other way. I couldn't

think of a thing that would have saved my swimming championship. It

wasn't a matter of luck. In fact, I'd been lucky not to get

caught. It must be the worst kind of FATE to be lucky and not be

able to enjoy it.

The

next day I did go back, found my pants where they had blown off the

standpipe, and the ladder over in the weeds. I dragged the ladder

back to Wilson's and sneaked my overalls into Mom's laundry basket.

So, no one suspected a thing. The next time I saw him, Bud explained

the reason he ran off was he thought he heard someone coming. I

wouldn't even talk to him about his lowdown trick or the standpipe.

I just acted mad and disappointed. I know he thought I'd chickened

out like he had.

I

kept it all to myself, brooding about the injustice of it all. I was

depressed for a week. Gradually, however, it began to take on

another meaning. When Dad bawled me out one morning and I got to

feeling down, I wandered up to the north end of town and looked up at that

big, ol', ugly black standpipe and got my spirit lifted just thinking

about how great that climb up and the night swim had been. After

that, if someone beat me in "shinney," or caught more fish, or made an "A"

in spelling when I got my usual "D," I'd say to myself, "Yeah, but you

never swam in a hundred foot of water."

Finally, I

realized it was best nobody knew but me. You see, I had this one

thing I'd done, this one thing I knew about me greater than what anyone

else knew about me. There were tons of bad things I'd done or

thought that only I knew about. When they came up in my mind, I

always felt little or foolish or just plain bad. Now, I had this big

thing no one else could ever be a part of. It more than off-set

those nagging sins.

As it was, I

knew I was the one-and-only-deep-hole-swimming-champion-of-Kansas!

It was enough to be the greatest, even if nobody else in the whole world

knew but me. It was mine and bad luck, FATE, nor nobody could take

it away from me.

For ordering information on The Preacher's Kid use this link to The Woodley Press.

Bobby